I had been wondering what ordinary people in India think about climate change. So last week on my ride home from the office, I asked my auto-rickshaw driver. He was a talkative guy, bearded, with black spectacles and a navy blue turban. He had been keen on identifying for me the many troubles a man like him endures on the subcontinent. “Too many people!” he shouted, his voice competing with the cab’s rattling frame and the bleats of oncoming horns. “Too much traffic!”

We swung around a landscaped rotary. I gripped my seat. A copse of date palms swerved by, and then a billboard: “Enrich Delhi’s Green Legacy.” I took the bait. “So what do think about global warming?” I shouted.

We swung around a landscaped rotary. I gripped my seat. A copse of date palms swerved by, and then a billboard: “Enrich Delhi’s Green Legacy.” I took the bait. “So what do think about global warming?” I shouted.

We slowed to a stop behind a row of cars and two-wheelers waiting at the light. He cut the motor. A small boy pranced into the stalled traffic and began turning cartwheels in hopes of a small remuneration.

“Yes, I know about that,” the driver said. “Too much warming. Too much heat.”

“But do you worry about it?”

“Me—no.” He fired the engine and frowned slightly. “You know, India has too much noise!” he shouted. “And too many dogs! Too many everything.”

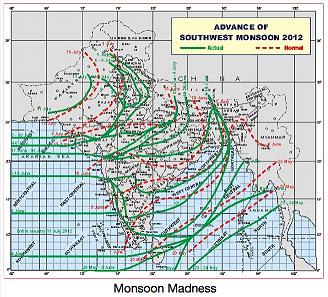

Full textNEW DELHI — Here’s what monsoon season looks like in India. This summer, the northern states have been lashed with rain. In the northeastern state of Assam, July rains swamped thousands of homes, killing 65 residents. Floods and mudslides in northeast India sent nearly 6 million people heading for the hills in search of temporary housing (a tarp, a corrugated roof) and government aid (when they can get it). In New Delhi, the monsoon hasn’t caused anything nearly as traumatic. But one cloudburst can easily flood roads and storm canals, sending bubbling streams of grease and sewage across the urban slums.

Haven’t heard about all this? Normally, I wouldn't have either. But this semester I’m living in New Delhi, near one of those storm canals, working as a Fulbright-Nehru Research Scholar affiliated with India’s Centre for Policy Research (another “CPR”). My plan is to examine the ways in which Indians are adapting to climate change, at the national, regional, and local levels.

Haven’t heard about all this? Normally, I wouldn't have either. But this semester I’m living in New Delhi, near one of those storm canals, working as a Fulbright-Nehru Research Scholar affiliated with India’s Centre for Policy Research (another “CPR”). My plan is to examine the ways in which Indians are adapting to climate change, at the national, regional, and local levels.

Perhaps no country in the world is as vulnerable on so many fronts to climate change as India. With 7,000 kilometers of coastline, the vast Himalayan glaciers, and nearly 70 million hectares of forests, India is especially vulnerable to a climate trending toward warmer temperatures, erratic precipitation, higher seas, and swifter storms. Then there are India’s enormous cities (home to nearly a third of the population), where all of these trends conspire to threaten public health and safety on a grand scale—portending heat waves, drought, thicker smog layers, coastal storms, and blown-out sewer systems.

Full textToday CPR releases a new briefing paper explaining how states can spearhead improving energy efficiency standards for home appliances. The paper, States Can Lead the Way to Improved Appliance Energy Efficiency Standards, draws on ideas discussed in Alexandra B. Klass’s article State Standards for Nationwide Products Revisited: Federalism, Green Building Codes, and Appliance Efficiency Standards. I co-authored today’s paper with CPR Member Scholars Klass and Lesley McAllister.

Traditionally a strongly bipartisan issue, support for energy efficiency has been eroded by anti-regulation sentiments. Without strong political support or adequate resources, the Department of Energy (DOE) has struggled to promulgate adequate efficiency standards. Regulatory efforts at the federal level have come up short, resulting in weak and delayed standards, or often no standards at all. In the absence of a dramatic shift in political will at the federal level, the most effective way to bring about improved efficiency standards and realize their attendant benefits will be to establish a system that retains strong federal standards while allowing states to set alternative, more stringent standards.

Such a system could be implemented by amending DOE’s existing regulations. First, DOE should clarify the existing state waiver process and respond more favorably to such requests so that states can successfully obtain waivers granting them permission to adopt improved appliance efficiency standards. Second, DOE should amend its regulations to allow states to adopt another state’s approved standard, thereby making improved standards available nationwide. Finally, DOE should ensure that there is only one standard in addition to the federal baseline for an appliance at any time.

Allowing states to take the lead in improving appliance energy efficiency standards will benefit consumers, manufacturers, and the environment. Consumers will save money on their electric bills and enjoy updated appliances at a lower cost as a result of improved standards. Manufacturers stand to gain from increased sales and lowered production costs. The environment will benefit from reduced natural resource consumption and lowered greenhouse gas emissions. Unfortunately, these benefits are not currently realized due to numerous delays at both the political and federal agency levels. These delays will result in at least $28 billion in unrealized energy savings by 2030. To avoid this result, DOE can work with states to allow them to take the lead in achieving meaningful efficiency gains without creating a 50-state patchwork of regulation for manufacturers.

Full textCross-posted from Triple Crisis.

Can we protect the earth’s climate without talking about it – by pursuing more popular policy goals such as cheap, clean energy, which also happen to reduce carbon emissions? It doesn’t make sense for the long run, and won’t carry us through the necessary decades of technological change and redirected investment. But in the current context of climate policy fatigue, it may be the least-bad short-run strategy available.

You may have lost interest in climate change, but the climate hasn’t lost interest in you. Once-extraordinary heat waves are becoming the new normal. Recent research demonstrates that by now someone “old enough to remember the climate of 1951–1980 should recognize the existence of climate change, especially in summer.”

Despite evidence of a worsening climate, the repeated failure of climate negotiations is sadly predictable. Real climate solutions require international cooperation, but inaction can be guaranteed by one country acting alone: No one else will accept significant costs for emission reduction unless the United States does. The world waited breathlessly for the first post-Bush climate meeting at Copenhagen in 2009; removing W. from the White House was necessary, but not, alas, sufficient for progress. Another breathless moment occurred as environmental advocates went all-out to pass a climate bill in Congress in 2010, accepted a series of dreadful compromises, and still failed miserably.

Full textCross-posted from Legal Planet.

There has been considerable discussion of Governor Romney's views about the causes of climate change and about policies such as cap and trade. It's not easy, however, to find detailed documentation. For that reason, I've assembled as much information as I could find about what Romney has said and done over the years, with links to sources (including video or original documents when I could find them).

Jan. 2003. Romney takes office as Governor of Massachusetts.

July 21, 2003. In a letter to New York Governor George Pataki, Romney says : “Thank you for your invitation to embark on a cooperative northeast process to reduce the power plant pollution that is harming our climate. I concur that climate change is beginning to effect on [sic] our natural resources and that now is the time to take action toward climate protection. . . . I believe that our joint work to create a flexible market-based regional cap and trade system could serve as an effective approach to meeting these goals.”

Jan. 2004 to July 2005. “During his first 18 months as governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney spent considerable time hammering out a sweeping climate change plan to reduce the state's greenhouse gas emissions.” (L.A. Times).

Full textToday CPR releases a new briefing paper exploring how the government can encourage, facilitate, and even demand actions from the different parts of the private sector to adapt to the changing climate. The paper is based on ideas discussed at a workshop CPR co-sponsored earlier this year at the University of North Carolina School of Law, which brought together academics, non-profit and business representatives, and government officials to wrestle with how government might positively shape the private sector response to the effects of climate change. Today’s briefing paper, Climate Change Adaptation: The Impact of Law on Adaptation in the Private Sector, was written by CPR Member Scholar Victor Flatt and myself.

Adapting to the impacts of climate change (not to be confused with the related pressing need to mitigate greenhouse gas releases) requires strategic planning and comprehensive action by both the public and private sectors, and each sector influences the other. For example, the private sector generates the overwhelming majority of economic output in the United States and is regulated for health, safety, and environmental purpose by the government. Land ownership is also largely private: roughly 70 percent of the land in the United States is held privately, and the government owns the remaining 30 percent. Effective climate change adaptation cannot happen without the cooperation of both sectors.

The workshop participants focused on adaptation that is influenced, motivated, or in certain cases prevented or constrained by the government, through laws, regulations, incentives, and policies with direct or indirect affects. For example, the timing of government actions, how the government balances between consistency and flexibility, and whether the government compensates the private sector can all affect how this sector responds to climate change.

Full textThe relentless heat wave that has plagued much of the country this summer, along with an accompanying paucity of rain, have plunged vast swaths of the United States into the most crippling drought in decades. Corn crops and now soy crops are withering, and commodity prices have risen dramatically. That could signal a sharp rise in domestic food prices just as the elections approach this fall, shocks to world grain markets fueled in large part by U.S exports, and significant financial losses to American agriculture. And that’s not to mention the horrific working conditions many farmers have to face every day in temperatures approaching or exceeding 100 degrees F.

Unfortunately, the weather forecast suggests that little relief is in sight. As of the middle of July, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had already designated 1,297 counties in 29 states as “primary natural disaster areas,” making them eligible for low-interest emergency loans and other forms of federal aid.. Here in my home state of Utah, almost every county is designated as a primary disaster area, and the rest are designated “contiguous” disaster areas. But we’re not alone. The same is true for all of the southwest (including California), parts of the northwest, the southern plains (including all of Texas), parts of the central plains, and all of Hawaii and much of the southeast as well. (For the current map, see here.)

Last week, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack said that one of his responses, in addition to disaster declarations, was to “get on my knees ever day and [say] an extra prayer.” On Monday, Secretary Vilsack took the more policy-oriented step of announcing added flexibility in USDA’s major conservation programs to help farmers struck by drought. USDA will allow areas usually off limits to farming as parts of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) to be used for haying or grazing; authorize similar flexibility to expand grazing, haying, livestock watering and other practices to farmers enrolled in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the similar Wetlands Reserve Program; and urge private crop insurance providers to voluntarily forego charging interest on unpaid insurance premiums for an extra month. Even if temporary, those changes highlight the political fragility of Farm Bill programs designed to protect the long-term ecological integrity of our agricultural ecosystems.

Full textCross-posted from Legal Planet.

In some situations, voluntary efforts leads other people to join in, whereas in others, it encourages them to hold back. There’s a similar issue about climate mitigation efforts at the national, regional, or state level. Do these efforts really move the ball forward? Or are they counterproductive, because other places increase their own carbon emissions or lose interest in negotiating?

A common sense reaction is that every ton of reduced carbon emissions means one less ton in the atmosphere. But things aren’t quite that simple. If we mandate more efficient cars, a number of other things might happen besides the immediate drop in emissions per mile: people might increase their driving because they don’t have to pay as much for gas; the same number of less efficient cars could be sold, but in other countries; or the reduced demand for gas might lower prices, leading to higher gas sales somewhere in the world. Other countries might feel that if we’re cutting emissions they can wait a little longer to address the issue.

There are also many reasons why our program might reduce emissions elsewhere. Automakers might prefer to produce the same models for multiple markets, here and elsewhere. Or the new technology may be appealing to consumers in other places. Other places might see our regulations and decide to copy them. And seeing that we are taking action could increase confidence that a bargain can be reached, improving prospects for negotiations.

There’s necessarily an element of speculation in all of this. We can’t run experiments in which sub-global mitigation takes place on some planets while others do nothing pending a global agreement. In a recent paper, I’ve tried to look at what limited evidence and modeling seems relevant. On balance, the optimistic view seems more plausible. Acting locally while thinking globally may not be the ideal strategy, but it’s the best we have right now.

Full textCross-posted from Legal Planet.

It got less attention than it should because it was upstaged by the Supreme Court’s healthcare decision, but last week’s D.C. Circuit ruling on climate change was almost as important in its own way. By upholding EPA’s regulations, the court validated the federal government’s main effort to control greenhouse gases. To the extent that the case got public attention, it was because the court affirmed EPA’s finding that greenhouse gases endanger human health and welfare. However, I want to focus on a much more technical, but practically very important question about the scope of the EPA regulations. Specifically, the issue is whether EPA was correct that the Clean Air Act unambiguously requires sources emitting more than certain amounts of greenhouse gases to use best available control technologies, even if they did not exceed threshold levels for conventional pollutants. What follows is necessarily technical, although I’ve tried to explain the issues so that interested non-lawyers can follow the discussion.

Some background is necessary to even understand the issue. As a key source of regulatory authority for regulating greenhouse gases, EPA has relied on the PSD (Prevention of Serious Deterioration) section of the Clean Air Act. The statute requires EPA to set air quality standards for certain key pollutants, the so-called criterion pollutants. The PSD provisions apply to areas in which those standards have been met for a particular pollutant. There are special requirements for new sources in such areas.

This brings us to the question of what any pollutant means. There are two relevant sections of the statute. First, under section 165, any “major source” must use the “best available control technology for each pollutant subject to regulation under this chapter.” Second, under section 169, a major source is defined as one that emits more than specified amounts of “any air pollutant.”

Full textCalifornia environmental justice groups filed a complaint last week with the federal Environmental Protection Agency arguing that California’s greenhouse gas (GHG) cap-and-trade program violates Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act, which prohibits state programs receiving federal funding from causing discriminatory impacts. They allege that the cap-and-trade program will fail to benefit all communities equally, and could result in maintaining and potentially increasing GHG emissions (and associated co-pollutant emissions) in disadvantaged neighborhoods that already experience disproportionate pollution.

While the complaint reflects real concerns about the distributional impact of a GHG cap-and-trade program on associated co-pollutants, it’s important to keep the complaint in perspective. Neither it, nor previous lawsuits, present the multi-faceted set of environmental justice arguments on GHG cap-and-trade. An earlier suit challenged the sufficiency of the state agency’s alternatives analysis under California’s environmental review law, and this claim raises potential disparate impacts under Title VI. The legal claims reflect available causes of action, and should not be taken as the full measure of the groups’ opposition to cap-and-trade.

For example, California environmental justice groups mistrust the basic effectiveness of cap-and-trade given a history of problems in RECLAIM, a southern California criteria pollutant trading program, weaknesses in the ETS, Europe’s GHG trading program, and the current “slack cap” in the northeastern states’ RGGI program. Another concern is that cap-and-trade programs lack the participatory features of traditional permitting processes. The greater administrative efficiency and flexibility that industry celebrates cut off the slow, individualized, public-hearing process that allows local communities to participate (however weakly) in the emissions decisions of the facilities in their midst. Thus, it would be a mistake to attempt to discern the complete “environmental justice” position on cap-and-trade solely from the causes of action articulated in the lawsuits.

Full text