In October, Senator Ben Cardin (D.-Md.) introduced the “Chesapeake Clean Water and Ecosystem Restoration Act of 2009,” signaling the beginning of a new era of federal commitment to Bay restoration. The legislation is a tremendous step in the right direction, and it includes many elements to help make the Bay Program and the Bay-wide Total Daily Maximum Load (TMDL) models for watersheds across the country. In addition to the inclusion of mandatory implementation plans and enforceable deadlines, the legislation also establishes a nutrient trading program in the Bay watershed.

Nutrient trading works where regulated entities are required to meet certain pollution caps, either in their National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits or in an applicable TMDL that is then incorporated into their NPDES permits. If the cost of implementing control measures is expensive, the regulated entities may seek to buy pollution credits from other entities. These entities, either other point sources or nonpoint sources, must first meet a baseline of pollution reduction themselves. Any further reductions below that baseline can be sold as trade credits, providing a financial incentive to participate in the trade program and pollution reduction. In Pennsylvania, where a state trading program already exists, one borough reduced by 35 percent the cost of meeting its permit caps by purchasing credits from a nearby farmer who converted 900 acres to no-till agriculture, reducing sediment in runoff.

Full textOn September 24, arguments began in Oklahoma v. Tyson, a 2005 lawsuit filed by the Oklahoma Attorney General against poultry companies operating in the Illinois River Basin. The lawsuit alleges violations of federal environmental laws, state and federal public nuisance law, and state statutes regulating pollution of waterways. Oklahoma’s legal strategy is unique: the state is bringing the suit under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, more commonly known as the Superfund Law) to target the nonpoint source pollution of water. Success for Oklahoma in this case would signal a serious development in protecting water from nonpoint source pollution.

The defendant companies – 11 poultry producers including Tyson Foods, Cargill Turkey , Peterson Farms, Simmons Foods, and others – contract with large-scale poultry farmers across the basin, which covers 1 million acres between Oklahoma and Arkansas. They provide the farmers with the chicks, feed, and other support while the farmers themselves actually own, operate, and manage the poultry operations. An estimated 1,850 poultry farms operate in the basin, generating nearly 345,000 tons of poultry “litter” each year. The farmers either apply it as fertilizer to their own lands or sell it to other farmers to do the same. Poultry litter includes fecal waste and poultry bedding materials, and contains such bacterial pollutants as E. coli, salmonella, and Campylobacter, as well as such nutrient pollutants as phosphorus, nitrogen, zinc, and copper.

In opening arguments, Oklahoma Attorney General Drew Edmondson asserted that this poultry litter has caused the fecal bacterial contamination of waterways in the Illinois River Basin. Heavy rainfalls wash the poultry litter into waterways, rendering the water unfit for consumption and human recreation, and causing unreasonable interference with the public’s use and enjoyment of the waterways, he said. Oklahoma’s lawsuit seeks a number of comprehensive remedies, including a permanent end to the practice of applying litter to the land around the poultry farms, and finding the companies liable for all past and future costs associated with restoring the health of the waterways.

Full textThis post is part of CPR’s ongoing analysis of the draft reports on protecting and restoring the Chesapeake Bay. See Shana Jones' earlier "EPA's Chesapeake Bay Reports: A First Look"

One of the continuing obstacles to cleaning up the nation’s waterways, including the Chesapeake Bay, is the pollution caused by non-point sources (NPS). In the recently released draft reports on protecting and restoring the Chesapeake Bay, the EPA attempts to address NPS in part by reinvigorating the “reasonable assurance” standard, and on this specific issue, the reports need improvement. Under the language in the draft report, EPA would fall short, as it has in the past, of fulfilling the promise of the standard. While an improvement on past efforts, EPA’s new definition of “reasonable assurance” provides only modest assurance that pollution from NPS will abate.

Unlike point sources (PS) of pollution that originate from discernible, confined, and discrete conveyances, nonpoint sources of pollution are diverse and discharge into water through runoff. While point sources require federal permits to discharge pollution, nonpoint sources have managed to continue unpermitted and unregulated, to the detriment of water quality across the country. To help manage NPS pollution, section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act requires states or the EPA to formulate Total Daily Maximum Load for impaired waters. A TMDL for a pollutant is set at a level to meet applicable water quality standards for a particular waterway, regardless of the source of the pollution. A point source must comply with a TMDL through mandatory permit limitations, while a NPS generally slides under the radar.

One way that the EPA has attempted to regulate nonpoint sources is through the standard of “reasonable assurance.” First introduced to the EPA vernacular in 1991, this promising standard to help control nonpoint source pollution has not fulfilled its potential. In the first attempt, EPA required states to provide it reasonable assurance that “nonpoint source controls will be implemented and maintained or that nonpoint source reductions are demonstrated through an effective monitoring program” in waters impaired by a combination of PS and NPS. However, if a state failed to provide reasonable assurance that the pollution load from NPS would be reduced, then the burden of pollution reduction fell onto point sources—effectively creating an escape hatch for NPS polluters. To seal the escape hatch, in 1997 the EPA reissued guidance that clarified the application of reasonable assurance to waters impaired primarily by NPS.

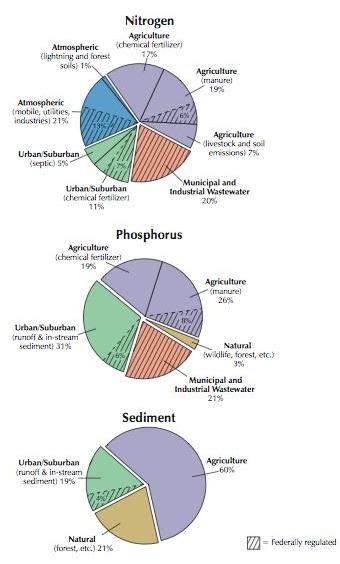

Full textOn Tuesday the Environmental Working Group (EWG) released a report on the status of state and federal agriculture policies for five Chesapeake Bay watershed states: Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia. The report focuses on agriculture policies that impact water quality and highlights a gaping hole in the regulation of animal-based operations. Past and ongoing efforts to improve the water quality in the Bay have focused on agriculture, where pollution control measures are fairly cost-effective (compared to wastewater treatment or stormwater runoff, for example). While these measures have reduced some of the nitrogen, phosphorous, and sediment pollution in the Bay, the agriculture sector still contributes the largest share of pollution: 42 percent of the nitrogen, 45 percent of the phosphorous, and 60 percent of the sediment.

For the report, EWG obtained data both on the number of permitted operations and animals covered by the federal and state permitting programs and from the 2007 Agriculture Census. The numbers of unpermitted dairy, beef, and swine agricultural operations are astonishing: in these five states, less than 2 percent of operations have either federal or state permits. This 2 percent covers a mere 35 percent of these animals. The permit rates for chicken operations are much higher: around 7 percent of the poultry operations are permitted, which covers 80 percent of the chickens. Even more astonishing, EWG had to use census data because “state program managers were unaware of the total operations and animals in their respective states or how many operations were eligible for a permit.”

The report finds that voluntary measures are not working for two main reasons: the farms that cause much of the pollution simply do not participate in the voluntary programs and the perennial lack of funding for these voluntary programs fails to cover the geographic areas and agriculture operations that are responsible for much of the pollution. Mandatory regulations of these operations are needed. President Obama recognized the need earlier this year with the executive order on restoring the Chesapeake Bay, and Senator Ben Cardin (D-Md.) is moving forward with a discussion draft for a Chesapeake Bay Reauthorization bill. But the EWG report notes that federal action alone is inadequate: the states must demonstrate the commitment and political will needed to restore and preserve the Bay.

EWG says this report is the beginning of a longer investigation into the actual effectiveness of these state and federal regulations. They're asking smart questions and finding unsettling answers.

Full textA feature article Sunday in the Philadelphia Inquirer, by Sandy Bauers, describes the impressive restoration of the Lititz Run, a stream located in the Lower Susquehanna Watershed in Pennsylvania. Lititz Run flows into the Susquehanna River, which contributes about 40 percent of the nitrogen in the Chesapeake Bay, as well as a significant amount of phosphorous and sediment. Efforts to curb runoff, change agriculture practices, and upgrade sewer treatment plants by the local community changed the run from a fetid, polluted waterway into a healthy, permanent habitat for trout. The water quality in the stream has improved significantly over the last ten years: nitrogen has been reduced by 47 percent, along with nearly 10-percent reductions in sediment and phosphorous.

The agriculture sector contributes the largest share of pollution into the Chesapeake Bay, amounting to 42 percent of the nitrogen, 45 percent of the phosphorous, and 60 percent of the sediment. The other giant contributors are the urban and suburban sectors, which together contribute 16 percent of the nitrogen, 31 percent of the phosphorus, and 19 percent of the sediment. While restored forests and stream buffers and other management practices have reduced the pollution load from agriculture, the pollution load from the urban and suburban sector has increased. The population in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed has grown by 8 percent, but the amount of impervious surface, or surface that prevents natural absorption of rainwater by the ground, has increased by 41 percent.

The agriculture sector contributes the largest share of pollution into the Chesapeake Bay, amounting to 42 percent of the nitrogen, 45 percent of the phosphorous, and 60 percent of the sediment. The other giant contributors are the urban and suburban sectors, which together contribute 16 percent of the nitrogen, 31 percent of the phosphorus, and 19 percent of the sediment. While restored forests and stream buffers and other management practices have reduced the pollution load from agriculture, the pollution load from the urban and suburban sector has increased. The population in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed has grown by 8 percent, but the amount of impervious surface, or surface that prevents natural absorption of rainwater by the ground, has increased by 41 percent.

CPR has worked extensively on Chesapeake Bay issues, proposing to strengthen accountability in the Bay Program and among states. In a June 2009 publication, Reauthorizing the Chesapeake Bay: Exchanging Promises for Results, CPR President Rena Steinzor and Executive Director Shana Jones recommended:

Today the EPA and other federal agencies will release a series of draft reports on the Chesapeake Bay examining issues such as the impact of climate change; stormwater management practices; and the existing federal regulatory programs, including the CWA. As mandated by President Obama’s executive order on the Chesapeake Bay, these drafts are the precursors to official reports due in November, and those reports will be subject to formal public comment. Chuck Fox, the EPA’s Senior Chesapeake Bay Advisor, has said that the draft reports may contain more provisions to deal with urban and suburban runoff from existing developments and to bring more concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) into compliance under the CWA.

Stay tuned for more soon on these draft reports from EPA.

Full textLast week, the Environmental Protection Agency agreed to set specific, statewide numeric standards for nutrient pollution in Florida, marking the first time the EPA has forced numeric limits for nutrient runoff for an entire state. This settlement, based on a 1998 EPA determination that under the Clean Water Act all states were required to develop numeric standards for nutrient pollution, has implications for the thousands of impaired rivers, lakes, and estuaries across the United States.

Under the Clean Water Act, states are required to establish water quality standards that consist of two components: a designated use and water quality criteria. The designated use identifies for what purposes the water body will be used, such as drinking water, recreational, or industrial use. Water quality criteria measures the chemical, biological, nutrient, and sediment composition of a water body and requires their levels to support the designated use. The CWA requires toxic pollutants to have specific numerical criteria. For other pollutants, the CWA permits narrative standards set on a qualitative, rather than quantitative, basis. Most states, including Florida, use narrative criteria for nutrient pollutants. Florida’s standard states, “In no case shall nutrient concentrations of a body of water be altered so as to cause an imbalance in natural populations of aquatic flora and fauna.” How is an “imbalance” measured? How can a present imbalance be compared against a past imbalance?

In the lawsuit, five Florida environmental organizations pointed to the obvious difficulties in enforcing this standard. This narrative standard, the groups stated in the lawsuit, contains “no measurable, objective water quality baseline against which to measure progress in decreasing nutrient pollution, nor is there any measurable, objective means of determining whether a water quality violation has occurred.” In fact, EPA itself recognized the importance of numeric criteria in facilitating development and implementation of pollution controls and pollution discharge permits and in evaluating the effectiveness of nutrient runoff minimization control programs.

Full textIn July, a federal judge settled a nearly 20-year legal dispute among Alabama, Florida, and Georgia over the use of water from Lake Lanier, dealing a tough blow to Georgia. The Army Corps of Engineers constructed Buford Dam in the 1950s, creating Lake Lanier as a reservoir for flood control, navigation, and hydropower. But Atlanta and its sprawling metropolitan area came to rely on the reservoir as a water supply, and Lake Lanier today supplies water to 75 percent of the city. In 1990, Alabama and Florida filed suit against the Corps and Georgia to stop Atlanta’s use of the reservoir.

The 97-page order from Paul Magnuson of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida is clear: Atlanta’s use of water from Lake Lanier as a municipal water supply is illegal and inconsistent with the original purposes of the lake. Georgia must get Congress to approve a change in use for water from Lake Lanier, and it has 3 years to do so. With this ruling, Alabama and Florida clearly have the upper hand. Without congressional approval or some other resolution, withdrawals from the lake must return to the levels of the mid-1970s. Thus, water deliveries to Atlanta would cease completely. Only two small cities that were originally allowed to use the Lake as their water supply would be able to continue water withdrawals. The court itself recognized this order as a “draconian result” but commensurate with “how far the operation of the Buford project has strayed from the original authorization.”

Tucked away at the end of this decision is the most telling paragraph. Judge Magnuson wrote:

Full textToo often, state, local, and even national government actors do not consider the long-term consequences of their decisions. Local governments allow unchecked growth because it increases tax revenue, but these same governments do not sufficiently plan for the resources such unchecked growth will require. Nor do individual citizens consider frequently enough their consumption of our scarce resources, absent a crisis situation such as that experienced in the ACF basin in the last few years. The problems faced in the ACF basin will continue to be repeated throughout this country, as the population grows and more undeveloped land is developed. Only by cooperating, planning, and conserving can we avoid the situations that gave rise to this litigation.

This is the fourth and final post on the application of the public trust doctrine to water resources, based on a forthcoming CPR publication, Restoring the Trust: Water Resources and the Public Trust Doctrine, A Manual for Advocates, which will be released this summer. If you are interested in attending a free web-based seminar on Thursday, July 30, at 3:00 pm EDT, please contact CPR Policy Analyst Yee Huang or register here. Prior posts are available here.

Groundwater, invisible as it meanders beneath our feet, provides about half of all drinking water in the United States and nearly all drinking water for rural populations. As water demand skyrockets, groundwater pumping rates far exceed replenishment rates. For instance, underlying the Great Plains is the Ogallala Aquifer, which has provided water for decades of farming. Now, this once dependable and seemingly infinite source is now disappearing in certain areas, reversing farming fortunes for many. In the Southeast, saltwater is entering the Floridan Aquifer due to low water levels, potentially contaminating the water supply for many communities.

Despite these threats and a future of increasing demand, many states have only recently begun to actively and comprehensively regulate groundwater, providing an opportune moment for water advocacy groups to push for public trust legislation. Historically, the public trust doctrine excludes groundwater from its protective scope. Yet applying the public trust to groundwater is a logical and sensible progression of the modern public trust doctrine, consistent with the focus on water. Groundwater is no less important to the public than the coastal and navigable waters that are protected under the traditional public trust doctrine. In many parts of the country, groundwater is the direct source of water for surface springs and other navigable bodies of water.

Full textThis is the third of four posts on the application of the public trust doctrine to water resources, based on a forthcoming CPR publication, Restoring the Trust: Water Resources and the Public Trust Doctrine, A Manual for Advocates, which will be released this summer. If you are interested in attending a free web-based seminar on Thursday, July 30, at 3:00 pm EDT, please contact CPR Policy Analyst Yee Huang, or register here.

Water advocacy groups and environmental attorneys have used a myriad of creative tools to protect water resources, including establishing minimum stream flows and lake levels, purchasing or acquiring in-stream water rights for environmental and recreational purposes, and using federal regulations to restore water for fish. While each of these strategies may be an effective microscopic solution, a macroscopic, overarching duty to manage water resources sustainably for both people and the environment is missing.

One solution to this missing duty lies in an ancient legal tool – the public trust doctrine. This doctrine holds that certain natural resources belong to all and cannot be privately owned or controlled because of their inherent importance to each individual and society as a whole. As a clear declaration of public ownership, the doctrine also reaffirms the superiority of public rights over private rights for critical resources. It impresses upon states the affirmative duties of a trustee to manage these natural resources for the benefit of the present and future public and embodies some of the key principles of environmental protection: stewardship, communal responsibility, and sustainability.

Full textThis is the second of four posts on the application of the public trust doctrine to water resources, based on a forthcoming CPR publication, Restoring the Trust: Water Resources and the Public Trust Doctrine, A Manual for Advocates, which will be released this summer. If you are interested in attending a free web-based seminar on Thursday, July 30, at 3:00 pm EDT, please contact CPR Policy Analyst Yee Huang, or register here.

As described in this earlier post, the public trust is similar to any legal trust. In the public trust framework, the state is the trustee, which manages specific natural resources – the trust principal – for the benefit of the current and future public – the beneficiaries. To date, the greatest and most consistent successes of the public trust doctrine involve cases of public access rather than resource protection – emphasizing the beneficiaries of the trust rather than fortifying the principal of the trust.

CPR’s forthcoming publication, Restoring the Trust: Water Resources & the Public Trust Doctrine, A Manual for Advocates, focuses on a novel use of the doctrine: to increase, fortify, and otherwise maximize the trust principal, or the natural resources protected by the doctrine. A handful of cases have succeeded in this particular application by requiring improved natural resources management. These cases fall into two broad categories of litigants seeking different purposes:

Illinois Central, the classic example of the doctrine as a limit on state action, arose from a populist movement that challenged the legislature’s grant of lakefront property to a private railroad company. Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387 (1892). In ruling that a state cannot wholly abdicate control of trust resources to a private entity, the Supreme Court laid the foundation of the doctrine as an upper limit on state power. In Arizona, Native American tribes successfully challenged the state legislature’s bill to eliminate the public trust doctrine from being considered in a water adjudication. The Arizona Supreme Court expressly stated that the doctrine is a constitutional limitation on legislative power to give away trust resources. San Carlos Apache Tribe v. Superior Court, 972 P.2d 179 (Ariz. 1999).

Full text